Listen now on Apple, Spotify or YouTube

In This Edition

- Does a game industry exist?

- Battlefield 6 numbers fall

- Spilt Milk’s Nicholas Lovell joins the Show

Hello, and welcome back to another fancy edition of The Game Business.

I’ve been dashing around the US this week, so we’ve got a slightly experimental edition today, where we explore the idea that there may not be a video game industry at all.

Game veteran and Spilt Milk Studios boss Nicholas Lovell joins us on the Show to discuss that very subject, and I’ve put together a piece on it below, too.

In addition, I touch upon the latest cuts at Ubisoft, Larian’s shifting position on AI, and the drop in Battlefield 6 players.

Enjoy!

There is no such thing as a video game industry

As headlines go, it’s a pretty ridiculous one for a game industry publication to write, but bear with me.

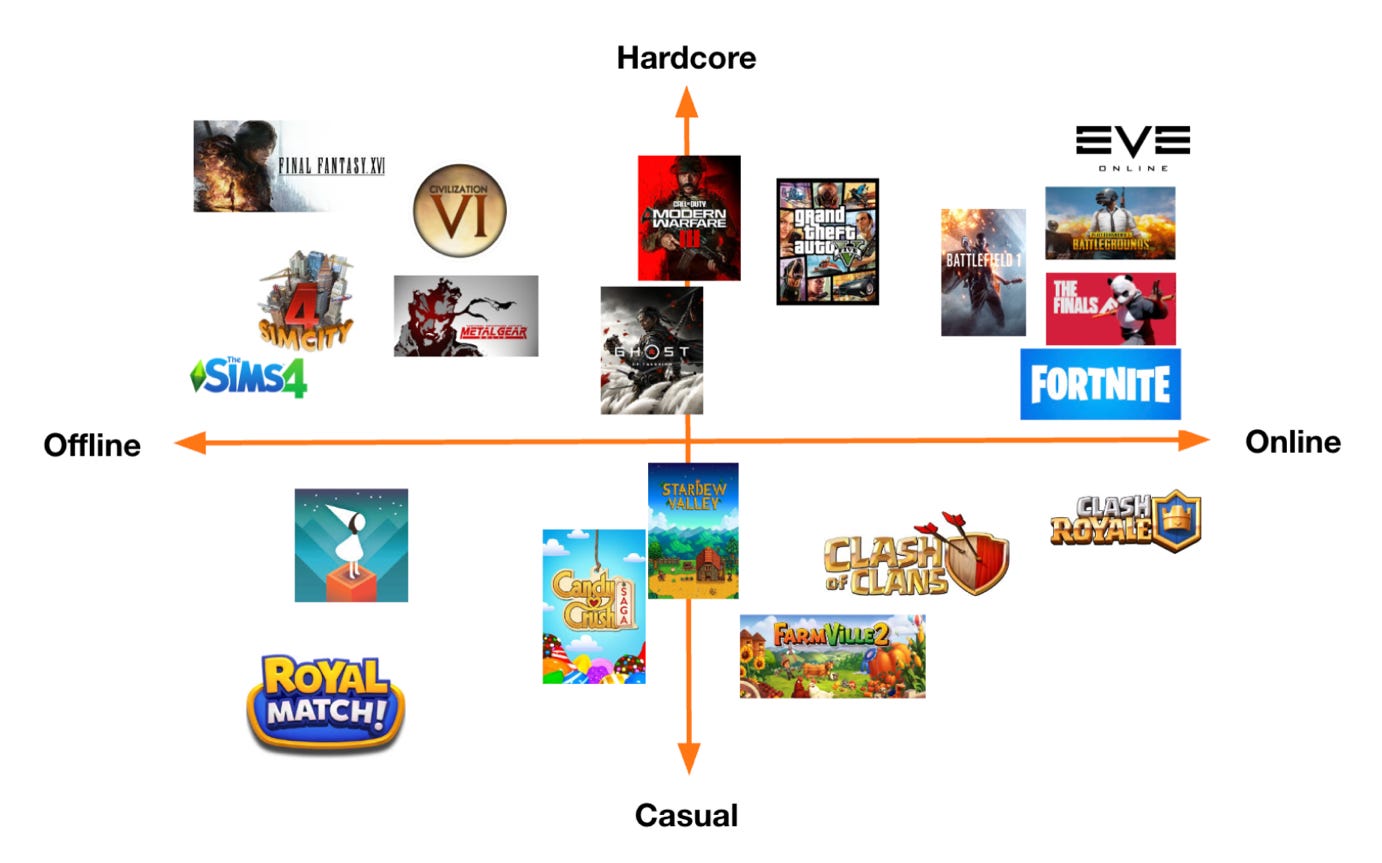

In 2019, Korean games giant Nexon was planning to re-organize. It needed to decide which projects to continue with and which ones to cancel. During this process, the company drew this on the board:

The graphic, courtesy of former Nexon CEO Owen Mahoney, posits that there isn’t one video game industry, but four. And they can be split as follows:

Offline Hardcore: Classic, singular, often story-based, games that are played alone.

Online Hardcore: Internet-based games that emphasize social connection and competition, over stories and visuals.

Offline Casual: Things like puzzle games that people play by themselves in (typically) short bursts, from solitaire to Candy Crush.

Online Casual: Connected experiences and challenges, usually on mobile, that are built around short play sessions. They lack the complexity of hardcore games.

There is, of course, games that fit into multiple areas. Call of Duty is both an offline and online game, for example. But it was a useful exercise for Nexon, which decided to focus its energies on the online hardcore business. Each of these segments are different to one another, including how the games are made, how they’re monetised, what players expect from them and the skillsets requires to deliver on them.

Nexon and Owen Mahoney are not the only ones who have argued that there is no such thing as a game industry. Nicholas Lovell, who is a game director, consultant, advisor, investor and co-owner of the indie developer Spilt Milk, also makes the same argument, although he splits the business differently.

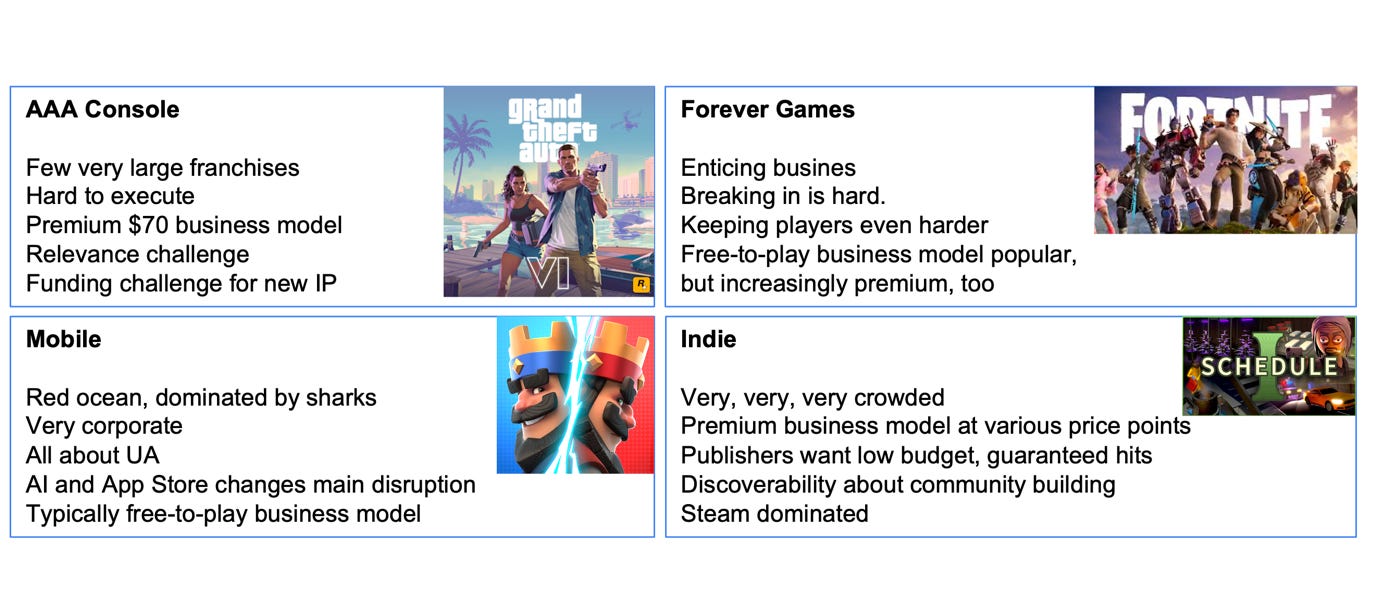

This Lovell model separates the industry into:

AAA console: These games are hard to execute and expensive to make. They’re typically $70+ to buy. The sector is less congested than the others, and they’re typically big franchises.

Forever Games: Often (although not always) cheaper than AAA to develop up-front, but requires significant post-launch investment. They can be free-to-play or premium (or a mixture of both), and potentially hugely lucrative with a sustainable income. However, breaking in is hard and keeping players is even harder.

Mobile Games: Less innovation going on in this space (broadly speaking). It’s dominated by large players, most of the budget goes on user acquisition, and these games typically use the free-to-play model.

Indie Games: Steam-focused and community-driven. Lower budgets and sold at lower price points. Publishers want cheaper, guaranteed hits. And it’s very, very, very competitive.

“Lumping games together as one industry is stopping our ability to understand what’s happening in the business”

Lovell joined us on today’s edition of The Game Business Show, and he suggests that the industry’s quest for legitimacy is why games are often bundled together as one sector. Doing this allowed us to make claims such as ‘games are bigger than movies’, which isn’t a particularly fair assessment. If we are treating interactive entertainment as one medium, then we should do the same for passive entertainment, too. And the combined industries of TV, movies and online video are significantly bigger than games.

“We were so busy trying to prove that we were big and important, we lumped everything together,” Lovell said on the Show. “And now as we’re starting to grow, it’s stopping our ability to understand what’s happening in the business, or where our competitive threats are, or what we should be making for our players. The troubles of AAA are not the troubles of Supercell trying to break out a brand new successful mobile game, or the troubles of Spilt Milk trying to get… I mean, we are pretty happy with 60,000 players. We’d be delighted with 250,000.”

Reframing the business

A popular conversation in video games right now is around player time. You’ve seen the headlines that claim that new games are competing for 12%, 14% or 17% - whatever stat you want to believe – of player time. This takes a wider view of the game sector, which points to how much time people are spending on big live-service games like Fortnite and Roblox.

It is useful to understand the macro social and economic trends within the entertainment business. Looking at things like the impact of short-form video, or other consumer behaviors, can help inform all of our decisions.

However, it’s easy to get lost in that conversation. If you’re making a single player narrative horror game, being told that Fortnite is sucking up so much time isn’t that useful, because you were never really competing for that time anyway. The motivation playing a competitive online game differs to why you might want to enjoy a story adventure.

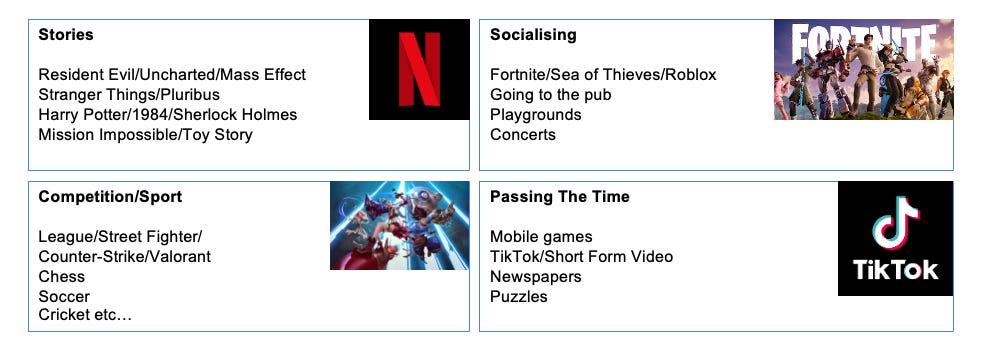

This led me to splitting the industry in an entirely different way. My thought experiment is that… what if there isn’t a video game industry at all (or a movie industry for that matter)?

Here’s my attempt:

My argument is that Resident Evil is more a competitor to Stranger Things than it is to Clash of Clans. Candy Crush is more directly competing with Tiktok than Fortnite. Roblox is more a rival to the school playground than Street Fighter.

I just picked four segments, but you could easily add more to it. I would argue there are games that are akin to toys, for instance. And there are other ways to categorise these player motivations, such as Professor Richard Bartle’s four-way ‘Bartle types’, or Quantic Foundry’s motivation model. Or you can just create your own based on your own world view.

These different ways of reframing the business helps us understand a few things. For one, being amazing at one type of game, doesn’t mean you’ll be amazing at another. How many single-player story studios have tried and struggled to develop and launch a live-service multiplayer title? Naughty Dog stopped mid-way through developing its The Last of Us online game with the realization that it wasn’t set-up to deliver it. Of course there are exceptions (take a bow Rockstar), but there are far more BioWares, Crystal Dynamics, Remedys and Rocksteadys. It’s not that these studios aren’t talented, it’s just their expertise lie in different areas.

Beyond talent, I also think reframing the business is something we need to be doing more with those outside of games, whether that’s investors, analysts, legislators, and even politicians. It’s not uncommon for me to speak to a non-games analyst who has made the mistake of looking at mobile games and console games through the same lens.

And so much of the proposed legislation facing games over the coming years is related to online titles, and it would be unfortunate if offline games got caught up in that, too.

But most of all, this process is about establishing a clear vision for what you’re doing. Knowing where to focus your energies, who your close competitors are, what the challenges are and what skills you need, is all going to prove essential in navigating this increasingly complicated and messy industry.

Not that it is an industry, of course.

Partner Message

Get 10% off Pocket Gamer Connects London 2026

Pocket Gamer Connects returns to London next week. The event takes place January 19 - 20 at The Brewery and Barbican Center.

The Game Business readers can also get 10% off the event. Simply click here, or use this code GameBusiness10.

Over 3,000 attendees are expected from more than 950 companies, with 290 speakers across the two days. New for 2026 includes The Transmedia Summit, which explores the crossover between film, TV and games. Plus the App Business Summit, which spotlights innovation beyond games, including AI, fintech, lifestyle and social apps.

Delegates get full access to MeetToMatch plus networking sessions such as Investor Connector, Publisher SpeedMatch, The Big Indie Pitches, and The Global Connects Party.

Battlefield 6 loses nearly 11 million players

After its record-breaking launch, EA saw a sharp drop in Battlefield 6 players over Christmas.

According to Ampere Analysis, 16.4 million people played the game across console and PC during December. 5.3 million were playing on PC, 4.7 million on Xbox and 6.4 million on PS5.

It’s still a big number, but it’s a hefty drop of 11 million compared with November, when it was the No.2 game of that month behind Fortnite. During December, Battlefield 6 was the sixth most played game, and had fallen behind rival shooters Counter-Strike 2 and Call of Duty.

The drop in players might be concerning, and certainly EA has a lot riding on Battlefield, but it still retains a large audience. And it’s not uncommon to see these fluctuations with online games, particularly early in the lifecycle when developers are still getting to grips with who its player base is, and what they’re looking for.

In related news, EA has delayed the launch of Battlefield 6’s season season into February, with the goal of ensuring it delivers a quality experience.

The firm wrote in a blog post: “We’ve continued to review community feedback and, in order to keep our promise, determined that our best path forward is to extend Season 1 and give ourselves extra time to further polish and refine Season 2.”

Meanwhile…

Ubisoft has cut 55 employees from its Ubisoft Massive and Stockholm studios, and 29 staff from its Abu Dhabi mobile team. These cuts follow the closure of Ubisoft Halifax, which impacted 71 staff. Ubisoft reduced its headcount by 1,500 for the 12 months ending September 30, and plans to make a further €100m in cost savings by start of its 2027 financial year.

In more layoff news, Meta has closed Deadpool VR developer Twisted Pixel Games, Asgard’s Wrath studio Sanzaru Games, and Armature Studio, which made the Resident Evil 4 VR game. The overall cuts to the division will impact 1,000 employees. Meta is shifting its metaverse focus towards wearables, such as augmented reality glasses.

Investment bank Aream & Co says that just $500 million in video game M&A activity took place in Q4 2025, a drop of 89% over the year before. However, the report reveals there were 39 deals in the period, which is a 34% increase. The firm says this represents a pivot towards “smaller targets”. Much of the M&A spend came from Asian companies.

Arc Raiders has now surpassed 12.4 million copies sold, Nexon has announced. It had previously announced the game had shifted 10 million copies by the end of December. It suggests the game’s sales momentum is increasing in 2026.

Baldur’s Gate 3 developer Larian will not use generative AI tools when creating concept art for its upcoming game, Divinity. “That way, there can be no discussion about the origin of the art,” said CEO Swen Vincke. It follows a Bloomberg interview last year when Vincke revealed that Larian was using generative AI “to explore ideas, flesh out PowerPoint presentations, develop concept art and write placeholder text”. However, he did stress at the time that no AI-generated content would make it into the final version of the game.

Mobile publisher Playtika is cutting 500 staff, reports CTech. It represents around 15% of its total workforce. Playtika boss Robert Antokol reportedly told staff that “our broad growth mindset is no longer sustainable,” and that it needs to make use of AI and automation to deliver more with fewer people.

If you’ve got any thoughts on today’s edition of the Newsletter/Show, I’d love to hear them. Drop me a note at chris@thegamebusiness.com.